Continuing the topic of why the success rate of new product and venture launches is so low and has not changed in the last 30 years, today I’m going to talk about what I call “Funding Gaps.”

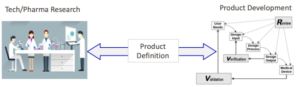

Funding Gaps exist in the space between an idea and a product that will be developed, scaled, and launched. In his classic book Crossing the Chasm, Geoffrey Moore talks about the chasm that exists in the market between today’s familiar experience, and a new experience made possible by a disruptive technology. Funding gaps are conceptually similar to the Chasm, but they occur before a product is launched; in a space that should be occupied by rigorous product definition. For example, here’s what happens in the medical device industry:

Notice there’s no real process for defining the right product before development occurs (note: asking users what they ‘need’ is not a substitute for fully defining a new product, as people usually ask for improved versions of what they already have). In addition to having no real process, the product definition phase typically is not directly funded. In essence, it’s invisible, and we have the data to show the ramifications of this invisibility.

CB Insights recently published a report on the top 12 reasons why startups fail, which can also be applied to any new ventures. Here’s the main summary chart on the landing page. (I highly recommend downloading the full report.)

What’s interesting to me is that taking the time to define the right product can reduce or even eliminate the risk of failing for 8 of the 12 reasons:

Failures can be directly avoided by defining the right product:

- No market need

- Got outcompeted

- Flawed business model

- Pricing/cost issues

- Product mistimed

- Poor product

Failures that can be indirectly avoided by defining the right product:

- Ran out of cash

- Pivot gone bad

The rest are due to unfavorable regulatory/regulation environments, or due to team issues.

It’s true that new ventures need funding to gain traction. So of course, the leaders of these ventures will do what is necessary to get the funding their companies need. And the way to get funding is to create something real enough to get data to support further investment.

My last post talked about “Data Traps” and how many commonly used product testing methods support confirmation biases and fail to reveal flaws in the initial concept. This is what typically happens when a robust product definition phase is rushed or eliminated. The ugly truth is that a large portion of investment dollars fund the development and scale of products that are based on not much more than hunches backed by data that supports initial confirmation biases.

No responsible investor wants to fund an unproven idea, but the product that is the fastest and easiest to develop is often not the right one. I’m sure that no responsible investor is consciously encouraging the development of the wrong product offering, but this is what is happening. The amount of time and money wasted on developing the wrong product is far greater than the amount of time and money that could be wisely spent defining the right product.

What can we do about it? We can start by asking better questions, funding the work to answer these questions, and refusing to fund continued development and scale until these questions are addressed. The questions should dig deep to reveal logic flaws and confirmation biases. Here are some examples to get started:

- What behaviors in the market are prompting the need for the idea?

- What is motivating these behaviors?

- What problem(s) should be solved to better satisfy these behaviors?

- What are all the ways to solve the problem(s)? Are we looking beyond our domain for how the problem could be solved? How is it solved in other industries? What would ensure a competitive advantage?

- What assessments have been done to know our solution is on the right track? What are the results telling us? What will we do about it?

- What will be our guiding criteria for success? How will this criteria guide our future decision-making?

The key here is not to focus on answering the questions themselves, but to assess the level of rigor to which they were fully addressed.

How are you addressing these questions in your work? What are others you might add?