Last week Adam Bryant wrote an article that described what he called, the “Logic Box”. Here’s how he defined it.

“The logic box is what you find yourself in when you think you are making analytically solid choices among various options but haven’t understood that the overall concept is misguided or flawed. There may be many defensible reasons that one possible choice is clearly better than the others. But the area in which you have chosen to operate is in the wrong box.”

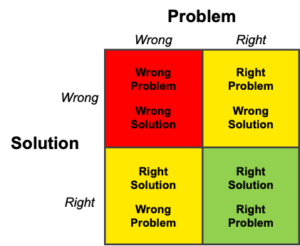

I see examples of the logic box all the time, and they typically fall into two categories: 1) Are we solving the right problem? And 2) Does our solution solve the problem? It sounds simple, but when launching a new product or service, most failures fall into one of those two categories, resulting in four main outcomes:

As I’ve mentioned before, the success rate of new solutions (as either a new product or a new company created to solve a problem in the market) is abysmally low – generally cited at less than 20%, and it has not changed in at least 30 years. [link to first post] Assuming most new products in the red box don’t launch (a big assumption, I know), that leaves up to 80% of new product failures launching from within one of the yellow boxes.

Nobody knowingly does this. A good product development process requires a lot of testing before launch. So why is this happening? I have observed that we land in the wrong logic boxes because we fall into what I call “Data Traps.”

We’ve become conditioned to the idea that more data is always better. But more data won’t help you to figure out if you’ve landed in the right box in the first place. As Adam Bryant points out, if everything we’re testing exists within the same logic box, then more data won’t help us. What more data can do, however, is solidify our confirmation biases and limit our willingness to examine our initial logic.

People don’t buy products because they have a higher score on a preference test. They buy products that fit their lifestyles and solve real problems.

In other words, if everything we’re testing lives within one of the yellow boxes in the diagram, then all we’re doing is determining the alternative that is the least wrong. Once launched in the market, even a mediocre solution from the green box will outperform the best solution from one of the yellow boxes.

Ensuring that your new solution lands in the green box requires a deep understanding of why the customer is making the choices they are making. This is why I continue to stress the importance of deep customer understanding to discern the tacit motivations that drive behavior. It is this type of understanding that ensures you position your solution in the green box from the inception of the development process – and this is equally true for the development of a product or a new venture.

Building the logic to establish the boundaries of the green box is a uniquely human skill. AI and machine learning are getting better all the time, but as long as humans are developing the algorithms that dictate their decision logic, we will not reduce the risk of landing in the wrong logic box.

We are always pressed for resources, and it’s easy to tell ourselves that it takes too long to do this deep work in the beginning. But the cost of developing the right product and the cost of developing the wrong product is the same. The time spent ensuring you’re starting off in the right logic box determines whether the money spent will become the sunk cost of a market failure, or the wise investment in a market success.

I make sure my clients land in the green logic box. What about you? How do you handle logic boxes and the data traps that can keep you stuck within them?