When I think about organizational control structures, an image of a topiary comes to mind. The growth of these plants is tightly controlled, and every aspect of their care and growth is planned. It takes several years before they are fully grown over the underlying frame, which eventually disappears as the plants fully assume their intended shape.

This evolution is similar to the way a company grows and scales their operations. The original idea around which the company was formed is eventually hidden. As with the topiary, day to day operations are about controlling growth to maintain the organization’s original purpose and goals. As with the underlying topiary frame, the original purpose becomes hidden as the organization matures.

In my last two posts, I talked about how power is shifting to create new sources of influence on organizations, and as a result, leadership of these influences is becoming more distributed. These power and leadership shifts can cause the existing control structures to become severely dysfunctional.

In times of disruption and change, we must also shift our perspective on what we should control to achieve our goals.

When these shifts happen, we need to take a step back and refocus on the underlying purpose and goals we’re trying to maintain. Refocusing to create completely new ways to achieve our purpose and goals can feel chaotic, as if we have no control over the end result. But this isn’t true. In this case, the image of a trellis is more useful.

With a trellis, the underlying structure visible, and can be altered if necessary. It gives us a large degree of freedom to determine what will grow best in new conditions, and we can see new ways to support this growth. If a plant doesn’t work out, it’s easy to try something new.

The trellis does not dictate how the plant grows, nor does it necessitate a specific maintenance process. It does, however, provide a solid structure and boundaries for growth. The organizational equivalent would be to provide clear goals and guardrails for a new direction, without trying to control how the goal is achieved. This is much more suitable during times of change.

Enabling this type of control requires different leadership skills. Leading a team of people who are skilled in executing a known process requires a focus on constant improvement to known benchmarks. On the other hand, leading a team of people to figure out what new benchmarks need to be created requires a focus on consistent assessment of our progress toward the goal – and the ability to assess whether the original goal itself should be modified.

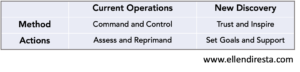

The image above compares these two types of leadership and control in very simple terms. Neither is always right or wrong, but the point is that they are very different. The real skill of senior leaders is to accurately assess what situation the organization is in and ensure the right people and control structures are in place to address it.

Feeling as if we lack control is unsettling, and when this happens it’s human nature to default to our comfort zones. The key is to realize that when we feel we lack control, we may just be trying to control the wrong things.

Have you seen examples of organizations trying to cling to existing control structures when they need to change? What about when different parts of the organization are needing different approaches simultaneously?