Part 1 Recap

Part 1 of this series introduced the struggle companies face as they try to ensure today’s success while keeping an eye on tomorrow’s survival, as referenced in the FT’s Corporate Longevity Series (#ftlongevity) by Michael Skapinker. It built upon ideas by Arie De Geus’ book The Living Company, and the Darwin/Megginson point that “[species] who survive are the ones who most accurately perceive their environment and adapt to it.”

It was exemplified by the untimely death of Polaroid, a company with a great vision that couldn’t adapt to its changing environment. This post will introduce a new paradigm for thinking about the progression toward a future vision, while continuing to optimize today’s economic activity.

Leaving the Future to Chance

Since there are no clear benchmarks for the future, planning for it is avoided because of the uncertainty of success. Ideally, a map of the future state would look something like this:

While it may seem appealing to leave future options open until they can become more concrete, this behavior locks a company into incremental improvements over what is done today. In reality it looks something like this, with potential futures evolving from the current business:

This works well until something (or someone) truly disrupts the market environment in which the company exists. If this happens (as suggested by De Gues), the company will likely die since they do not keep their “left of the line” skills up to date. It simply takes too long to reinvent, and by the time they do, the market has passed them by.

Roadmap to the Future

The fact that today’s measures of economic activity cannot be applied does not mean that progression toward the future cannot be planned. It is possible to deliberately create an ideal future vision that guides new, continually disruptive steps toward realizing it. Ideally a map of the future state based on this focus would look something like this:

As with the previous model, reality looks a little different. In this case, the parameters dictated by the vision remain the same, it’s just that the evolutionary path is not so linear:

In this model, each step along the way gets closer to the vision, but the type of offering, enabling technology, and specific success criteria can (and should) change as the market evolves. Although the market evolves in many possible directions, a company that’s aligned with a future vision evolves within parameters consistent with its identity. Appropriate metrics specific to each step are developed to ensure optimization as long as the economic activity is viable in the market.

Two Examples

Let’s revisit the Polaroid example. Imagine the guiding vision “to see the picture now”. Does this vision provide a goal against which we can assess viability of new ideas? Yes. Does it dictate how to accomplish that job? No. Imagine what else could have pursued to enable this vision. Virtual Reality? Holograms? The future vision could have been enabled by many new technologies well into the future, while still allowing for optimization of current activity along the way.

In contrast, consider the current company, Netflix, which delivers “flix” via a network. As technology has evolved, they have already gone through a couple of cycles of reinventing the way in which they deliver “flix” via a network. Their specific offering has changed, while the value promised by their vision has remained the same.

As the Netflix example also shows, it is not easy to balance the optimization of the current business while inventing new forms of value, and they have several battle scars to show for it.

Does it really need to be this hard? I think the answer lies at the source of what makes it so difficult. Is it because this type of balanced behavior goes against the current norms of running a business? Or is it too much to expect a company to become proficient at two fundamentally different types of focus?

Today’s Opportunity

I believe that the shorter product and company life cycles present an interesting opportunity. No longer able to complacently optimize current economic activity for several decades, corporate leaders will need to choose between a faster life/death cycle, or become proficient at a more balanced approach.

This is not a new dilemma. De Geus cites the tension he experienced between the Strategic Planning (Financial) and the Scenario Creation (Future Vision) groups at Royal Dutch Shell. Because the future scenarios were often too fuzzy to prescribe specific action, he often witnessed decision makers siding with concrete financial plans that were ‘closer’ to the business. No matter that they frequently turned out to be wrong. (An experience many of us may find familiar.)

“It is better to be vaguely right than exactly wrong.” – Carveth Read

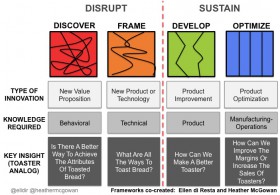

In the years since De Geus’ book was published, I have been privileged in my work with world class clients to have been able to create tools and metrics to make our “right” options less vague, and our “wrong” options more obviously wrong. My next several posts will introduce these tools and will discuss their use in helping companies to balance these two areas of focus toward a future vision.

Image credits: Frameworks co-created by Ellen Di Resta and Heather McGowan