“Why can’t I see the picture now Daddy?”

According to the famous legend, this was Edwin Land’s inspiration to create a product and company that became one of the world’s most recognizable brands – Polaroid. It’s an old example, but it’s one of the best examples of a future vision that by which to guide a company. There are many confounding reasons that contributed to the demise of the company, but the short answer is – they were disrupted. They were disrupted by a technology that could have enabled the original vision even better than the most advanced instant film ever could. But they missed it.

Disruption has become one of our favorite business buzzwords. The Google dictionary shows that the use of the term disruption has increased rather dramatically in the last 50 years.

The same Google dictionary defines disruption as a “disturbance or problems that interrupt an activity, event, or process.” But if disruption happens as much as the word is used, it seems like the new norm.

How would our work need to change for disruption to go from being an interruption of what we do, to becoming the core of what we do? Could that even happen?

I think about disruption in business a lot, as most of my clients recognize the threat of shrinking product life-cycles driving the need to invest in new opportunities that may disrupt their current businesses. In just one example, beyond Moore’s Law, Ray Kurzweil predicts that within the next 50 years, machine intelligence will be more powerful than all human intelligence combined.

Our current products are dying right before our eyes. And the companies that make them aren’t far behind.

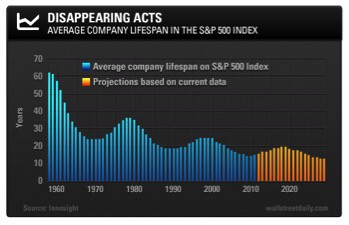

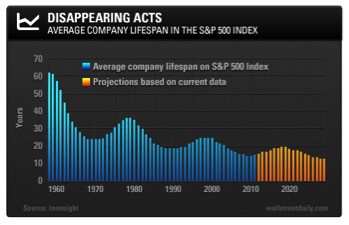

Innosight, the consulting firm founded by Clay Christensen, plotted the average lifespan of a company on the S&P 500 Index, revealing that it is less than a third of what it was in 1960.

There has always been tension between the competing needs of investing in future opportunities while ensuring that the current business thrives. Shorter technology and product life cycles only increase this tension as companies struggle to thrive in the short term while seeking opportunities for the next new thing – whatever that may be.

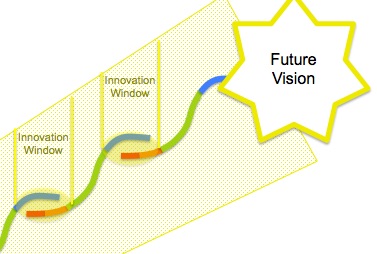

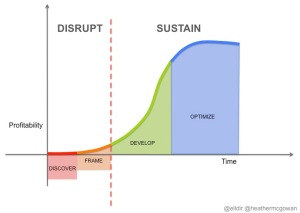

When I work with my clients, I describe the different types of innovation as illustrated in the model below, and as discussed in a previous post:

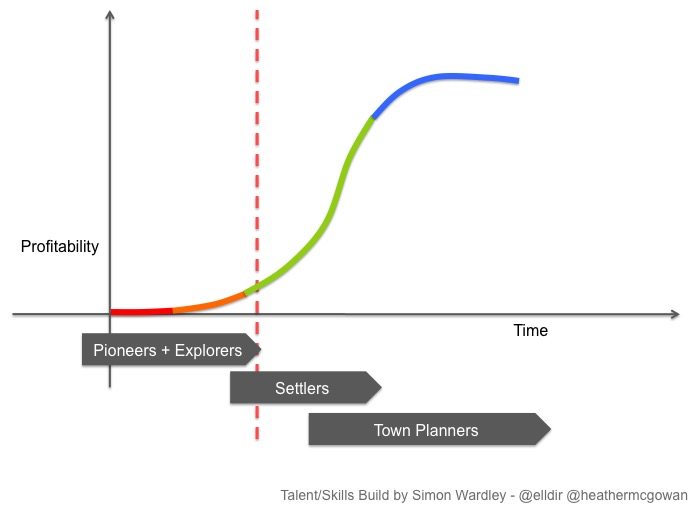

As illustrated by the model, there is a big difference in the focus and mindset between the work that exists “left of the line”, and the work that exists “right of the line.” These activities map against a typical product life-cycle curve in the following way.

In the past, a company could reasonably expect to spend several decades continually cycling through incremental improvements that require “right of the line” expertise. Their “left of the line” organizational muscles start to atrophy. Simon Wardley describes these skills as analogous to the development of a new town, and looks something like this:

When the threat of disruption is on the horizon, the company struggles to come up with their next big idea as they typically apply more “right of the line” skills. This creates tension that can be paralyzing.

I am always looking for new ways to ease this tension with my clients as I help them to strike the right balance between Exploring, Settling and Planning. To that end, I recently came across the FT’s Corporate Longevity Series (#ftlongevity), which asks the questions “What are the secrets of long-lived companies?”, and more importantly, “Are they always a good idea, or is a faster birth and death cycle better for the economy?”

The series is being led by Michael Skapinker, and in this article about the series, he cites an influential work on the topic by Arie De Geus called “The Living Company” from 1997. Though written in 1997, De Geus’ work is a great refresher when we consider the current business environment.

De Geus states the following:

“…the main reason companies die is because their managers focus on the economic activity of producing goods and services, and they forget that their organizations’ true nature is that of a community of humans”. To that I would add the phrase “…that serves a community of humans that make up their market.”

An old idea

This is very consistent with Darwin’s theory for why species avoid extinction. Leon Megginson paraphrased it this way “those who survive are the ones who most accurately perceive their environment and adapt to it.”

In other words, if you can’t adapt, you will be disrupted. And if you’re only focused on optimizing what you do today, you can’t adapt. Most business leaders understand this point, which is why disruption has become such a hot topic.

I believe that what keeps company leaders from striking the right balance between today’s success and tomorrow’s survival is that there are currently no broadly accepted approaches for defining success in the future. If it can’t be defined or measured, then it won’t be done.

My next post will introduce my approach to continuously disrupting the current business in a progression toward a future vision. In subsequent posts, I will introduce tools and metrics to make the development of new ideas with greater confidence in their success and relevance.

Image credits:

Google Dictionary definition – Disruption

Frameworks co-created by Ellen Di Resta and Heather McGowan